Commodore Format Power Pack 4 (Commodore Format, 1990)

My true C64 'golden age' begins.

16 Sep 2021 | by njmcode | 7 min

- Genre:

- Action | Platform | Horror | Sports | Racing

- Format:

- Cassette

- Developer:

- Various

- Composer:

- Various

- Publisher:

- Commodore Format

- Released:

- 1990

- Tags:

- compilation | cover-tape | demo | movie-tie-in | multiload | single-player

Memory

I don't remember how I got my first copy of Commodore Format magazine.

I probably I saw it in a newsagent in my home town, spotted a C64 tape mounted to the cover, and begged my parents to buy it. Or perhaps it was a gift from them. I can be crystal clear in one regard, though: it was the most important thing I ever did as a C64 owner.

Much of the nostalgia I serve here at The Raster Bar is a loose collage of overlapping memories. Events and eras mesh and collide together, out of sequence, like Polaroids spread out on the floor. My first purchase of CF from Issue 4 is a welcome anchor to the timeline: it was the January 1991 issue, released the month before in a strange quirk of UK publishing norms.

Xmas, December 1990. I was nine years old, still in primary school. I'd had my C64 for a while, and was glued to it whenever possible. I'd consumed every piece of content bundled with our original purchase, and had obtained several new titles since. But software remained the bottleneck. Today, throwing down the guts of £40+ for a AAA title is the unfortunate standard. Back at the dawn of the 90s, even £3.99 for a budget title was a lot of money to a kid, with the added fear of buying a bad game based on a misguided hunch or deceptive box art.[1]

Discovering Commodore Format was the key to a whole new world of not only C64 software, but C64 culture. The monthly covertape, dubbed the Power Pack, was the obvious draw, but in the magazine's glossy pages I now had access to reviews, opinions, walkthroughs, technical knowledge, humour - everything I needed as a burgeoning C64 obsessive. It started a journey that would carry through to my early teens, help forge lasting friendships, and set me on the career and creative paths I choose to walk today.[2]

Back in late 1990, though, the main attraction was Power Pack 4, with its two full games and two demos.

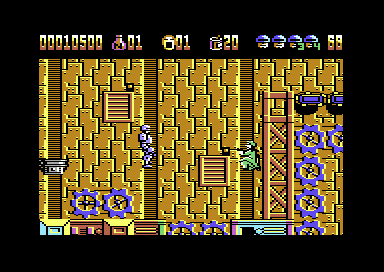

RoboCop 2 was first up. This brief one-level demo from Ocean saw the titular cyborg rescuing hostages, collecting 'Nuke' drug canisters, and shooting criminals. The industrial factory setting was the deadliest hazard, with electrical arcs, machine gears and crushing pistons all causing instant death. The biggest initial obstacle, though, was RoboCop's handling. The inertia with which he moved gave a suitably-weighty feel to the proceedings, but was troublesome for the platform shoot-'em-up gameplay. Robo could pick up speed and leap surprisingly far, and even had air control, but much of the demo's difficulty was in accurate positioning and timing of said jumps, in the face of narrow ledges, timed hazards, and even moving platforms. The visuals were garish but pleasing, and the FX were crunchy. Mastering the demo took a little while, but I could eventually speed-run it, and continued to wring as much enjoyment out of the short snippet as possible, messing around on the moving platforms, avoiding bullets til the timer expired.

Cosmi's Beyond The Forbidden Forest felt unlike anything I'd played thus far on the C64. An immediate air of dread was established with moody, storm-blasted intro credits, giving way to a chunky and highly-atmospheric full-screen forest environment. Controlling a lone archer, the goal was to collect golden arrows by slaying hideous oversized beasts. Doing this, according to the magazine instructions, would eventually grant access to the second half of the game and a showdown with the feared 'Demogorgon'.

So there I was, wandering the dread woodland, spine-chilling music lending genuine tension. I practiced the unique, awkward aiming system, expecting an attack at any moment. I steadied my nerves. And then... nothing. I ran through the forest, the environment looping around, but none of its monstrous inhabitants appeared. Losing patience after tens of minutes, I started pressing random keys... whereupon a giant scorpion entered stage right and savagely mutilated my unwitting archer in an orgy of pixellated gore. The Game, as the failure screen tragically proclaimed, was Lost. And I was scared.

What followed was swift and messy death at every turn: eaten alive, drained of blood, torn to shreds, as horror synths blared.[3] I soon abandoned my first attempts, but over the months to come I returned to master the game despite my fears. Dispatched monsters yielded golden arrows that granted resurrection, and were - again, according to CF's instructions - the key to accessing the mythical 'underworld' portion of the game. Day became night as I fought on, the chill blue of the game's sky yielding to blood-red sunset and eventually darkness. I was in the zone, grim determination in my veins: no enemy could touch me. So I fought, and killed, and persisted. Yet Beyond The Forbidden Forest refused to acquiesce, keeping its secrets from me no matter how many beasts were slain or arrows won. I eventually gave up and reset the machine, leaving my archer stranded in the cloying, infested black for all time. Though I didn't know it then, my ultimate nemesis in the game was Commodore Format's instructions. But I'll get to that later.

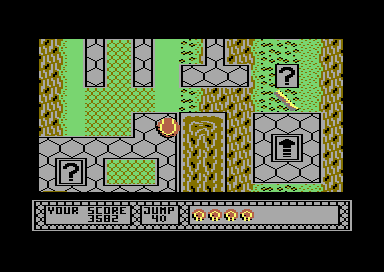

Side B of the tape offered a vibrant change of tone. Gremlin's Bounder was another unqiue experience, this time a rare top-down platformer starring a perpetually-bouncing red tennis ball. The screen force-scrolled at a slow yet inexorable pace past complex arrangements of platforms, suspended over dizzying canyons. You controlled the ball, guiding it as it bounced around, using air control, launch pads and mystery powerups to get to the goal without plummeting. Impassable barriers and a cast of strange, abstract enemies threatened your progress, while a lazy ditty soundtracked your journey onward.

Bounder was immediate, addictive fun from the moment I played it. The constant bouncing of the ball took a moment to adjust to, but its steady rhythm became the heartbeat of the gameplay, as I struggled to stay ahead of the scroll and get to the goal. The bonus round, where you had limited bounces to collect points, and the overall 'mystery prize' nature of the powerups gave the game a polished arcade feel, boosted by its impressive parallax effects. Despite its whimsical concept and presentation, it could be fiendish. I never finished it on my own, eventually relying on a POKE cheat printed in the magazine, but the struggle to get beyond the third or fourth stage was always a rewarding and entertaining one.

The tape concluded with a 'rolling demo' of the upcoming Lotus Esprit Turbo Challenge - a non-playabe showcase of its split-screen road-rendering effects. I hadn't yet become aware of the demoscene, so the idea of just watching the C64 'do' something without interactivity was unsettling to me, though the graphics and sonics were very high-quality. Of course, I childishly hoped that I could somehow control the demo anyway, and fruitlessly waggled the joystick in both ports, hoping for a miracle. It was the only part of the tape I never returned to having viewed it once or twice, preferring the other three offerings on my many subsequent plays.

Analysis

Power Pack 4 began the transformation of my C64 software collection and how I obtained it, and set me on a monthly cycle of eager anticipation and reward. Wondering what treats awaited me when the next issue of CF landed in the newsagent was a consistent source of excitement through the magazine's five-year lifespan. As the first Power Pack I owned, I have an inherent nostalgia for its contents, but the standalone games in particular deserve their own credit.

1985's Beyond The Forbidden Forest is clearly an early and effective example of what would become 'survival horror' in the 90s. It's all there: a disempowered protagonist, deadly monstrous enemies, restrictive controls, spine-tingling audio, and Scenes of Explicit Violence and Gore. It no doubt planted the seed that would grow into my love of Resident Evil, Silent Hill and its ilk on the consoles of the future. Sadly, CF's printed instructions for the game left out the method to access the 'underworld' section, thus preventing my progression, well, beyond the forest. In the intervening decades I've watched YouTube longplays, and remain impressed at the HUD-less blocky-yet-cinematic approach, undulating fantasy soundtrack, and late-stage full-screen horrors I missed out on. What I did play of it, though clunky, was compelling and nerve-wracking, a real test of mettle against erratic movement and one-hit kills. The general concept remains potent and ripe for remake, and the legions of indie 'rural horror' titles that have sprung up in the current VR age surely owe a debt to Cosmi's game.[4]

Bounder's charm still holds up well today, though the controls sometimes work against the player. The choice of vertical scrolling and its inherently more limited field of view can also grate. It's still a polished and well-crafted challenge, worthy of replaying and conquering, and would likely work very well as a mobile game with touch controls. It spawned a sequel (and future Power Pack game), Rebounder, which gained multi-directional scrolling, branching paths, boss fights and a futuristic setting, but lost nearly all of its progenitor's charm in the process.

I eventually played the full cartridge version of RoboCop 2 several years after its Power Pack 4 appearance. The demo was a decently representative slice of the whole: slick (despite some sprite multiplexing issues), playable, but also frustrating, repetitive and lacking atmosphere. It was a more complete game than its C64 prequel, yet devoid of the source fidelity and moody aesthetics that were the latter's only real plus points.[5] I never even considered obtaining the full Lotus Esprit experience; perhaps rolling demos were not an effective marketing tool for joystick-happy, gameplay-hungry consumers.

Better writers than I have exhaustively covered CF's content, history, and place in the commercial and social context of the era. I can't recommend the Commodore Format Archive site highly enough - everything you could reasonably hope to know of the magazine is documented there. I will no doubt cover CF more in future posts, but in summary, for now: it was an indelible, beloved influence on my growth as a C64 fan and as a young person. I eagerly collected (and, at time of writing, still inexplicably own) every CF covertape from this issue onward, but Power Pack 4 will always be the 'original' for me.

njmcode